Faith In Action.

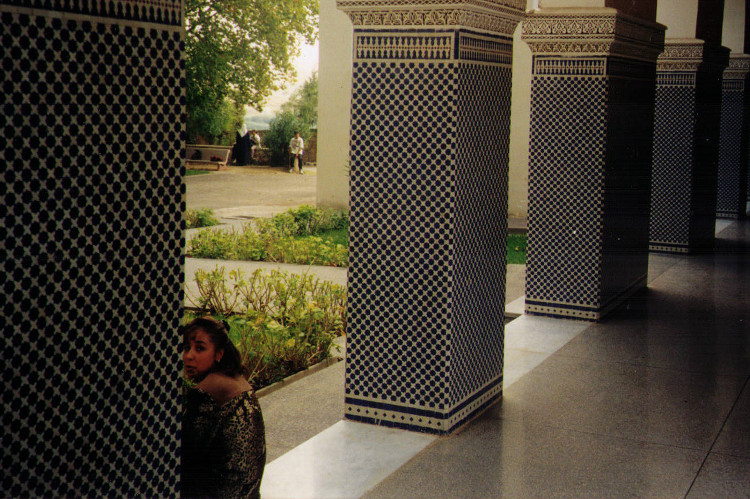

My books have a contrarian flavor: profiles of innovative, maverick scientists in the Soviet Bloc (Communist Entrepreneurs: Unknown Innovators) when the popular view was one of technological incompetence in the communist world; Muslim-Christian harmony (Monks of Tibhirine: Faith Love and Terror in Algeria) when people were touting irreconcilable differences between Islam and the West, and now Commander of the Faithful: A Story of True Jihad. Abd el-Kader was a warrior, statesman, scholar who combined deep religious faith with chivalrous humanism and intellectual openness that made him a hero in both the East and West. Commander of the Faithful is the third book of an Abrahamic trilogy that began unwittingly with Stefan Zweig: Death of a Modern Man.

Thinking back, I have realized that my last three books have a common thread. Indirectly, they are about struggle and the role of faith in guiding and sustaining people in desperate times. The stories have moved me from being an agnostic to a believer in the omnipresence of divine wisdom—accessible if our antennas are tuned, and requiring ceaseless effort.

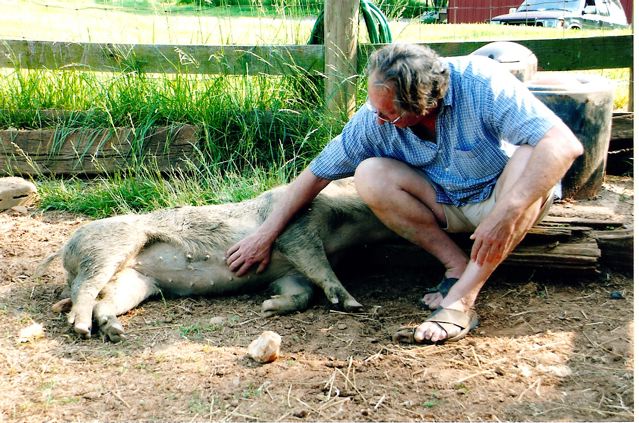

Of all God’s creatures, I find pigs among the most appealing..being my closest relative in the animal world, and having provided me with a new aortic valve to extend my writing career. My next book will be “Pigs Are Us.”

Author Q & A

I was drawn to the story because for me it represented a great adventure, one that was both spiritual and political. Through this story I wanted to understand how it is that religion can be a force for so much good and for so much evil in the world. Through the monks, I wanted to share in an expression of the Christian faith that I found very appealing — what I consider a real Christianity of truly universal, brotherly love, where it was lived, not preached, and where its practice by members of the Church was viewed simply as a sign of God’ s love for Muslims and for all people of good will. At the same time, I wanted to gain insights into the Muslim world and the religion of Islam, seen through the eyes of sympathetic Christians. Politically, I wanted to understand the violence occurring in Algeria, which appears to be a microcosm of the conflicts within in the larger Muslim world.

Also, I went to a boarding school where for six years I lived in conditions that today would be considered monastic. It was a good place for me to have spent those years and may explain my vague but long-standing interest in monks.

The story of the monks also demonstrates the need to maintain a very differentiated picture of Islam and of Muslims. There are as many different kinds of Muslims, just as there are different kinds of Christians. And to remember that violence does not just happen. It is a fever rooted in a sick, festering, societal situation that has been ignored. Islamic political violence is a form of desperation in the face of injustice or the hypocrisy of the governments, which have become insufferable to certain elements in society.

Sept.11 is also a reminder of what dangerous weapons holy scriptures are in the hands of those full of anger and hatred, and whose leaders manipulate scripture as an a la carte menu to serve political purposes. They can often skillfully convert the anger of the poorly instructed (in religion) into an expression of holy righteousness. St. Benedictine warns his monks of “the zeal of bitterness” that leads to Hell.

“Man is a Religious Animal. He is the only Religious Animal… He is the only animal that loves his neighbor as himself and cuts his throat if his theology isn’t straight.”

Mark Twain